Diminishing Marginal Utility is one of the Core Concepts of Economics

One of the underlying principles that help free markets in attaining efficiency in allocating resources among people is the principle of diminishing marginal utility. For most economic goods, the utility derived from the first unit of an economic good is more than the next. This difference between marginal and average utility derived from a unit is a defining feature of economics.

Consumption is one of the four basic economic actions that economic agents can undertake in respect of any economic good. However, unlike other economic agents, consumption is a characteristic of real human beings. In other words, companies do not consume economic goods in a strict sense of the term, since they do not have the capability of becoming better off by consumption. This capacity of becoming better off by consumption is the very basis of all economic activities, since all economic activities are finally aimed at consumption of economic goods by human beings and thereby making their lives better off.

When we compare the value, cost and price of an economic good, it is the value that corresponds with the betterment achieved by the person consuming or having it. This improvement in well being is also known as the utility derived from that good. This utility is largely subjective in nature, and depends upon preferences of an individual and his circumstances.

For instance, a bottle of water is likely to have a far more utility for a thirsty person searching for water in a desert rather than a person struggling to get out from a flooded locality.

The utility derived by an individual from a unit of a specific economic good also depends upon whether that individual already has any units of that good. This brings in the extremely important concept of marginal value or marginal utility, which is one of the core principles of economics that differentiate economics from finance.

The value of a shirt for a person who already has several of them would be different from the value of a shirt for the same person if he had none. If a person buys several units of the same good, it is very likely that the value of the first good that he buys or consumes would be different from the last unit of that good that he buys or consumes.

The value or utility that is derived by an additional unit of that good is known as the marginal utility.

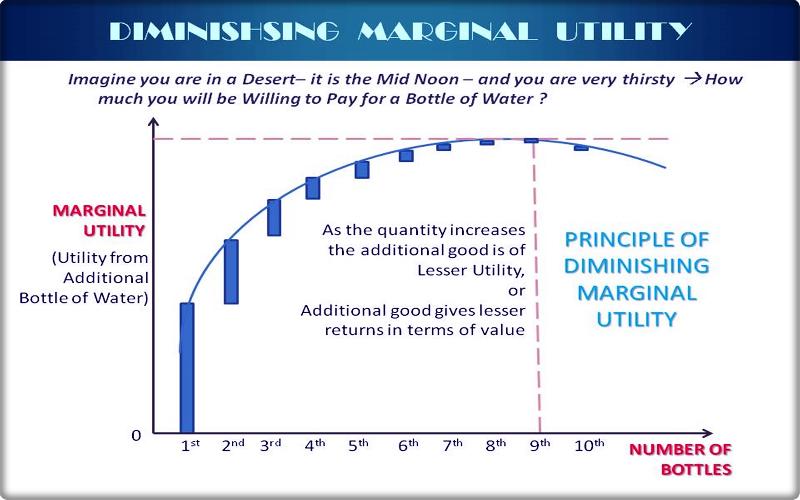

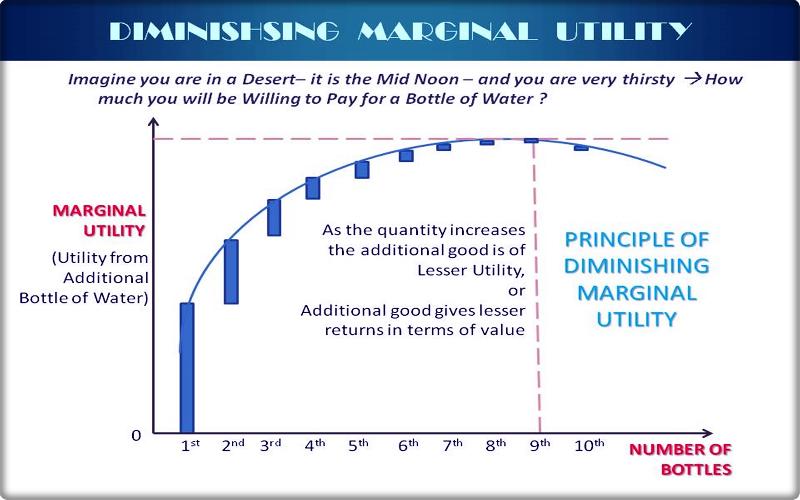

Consider a thirsty person in a desert wanting a bottle of water. The first bottle of water for him will carry a lot more value or utility than the second bottle. The second bottle will have more value than the third, which in turn would have more value than the fifth bottle. As he continues to accumulate water bottles, a stage is likely to come where the value from an additional bottle of water will become so low that it may not be worth the trouble to carry it. At this stage, even if water bottles are available freely, that person would be unwilling to carry additional bottles of water with him.

In this example, we can see that the marginal utility of the first bottle is very high and this utility falls with every successive bottle, till it falls down to a level that either approximates zero or falls below the costs involved in carrying it. This same principle is generally applicable in case of all economic goods that can be consumed.

One can argue that this principle is not applicable to money, since human greed to accumulate more never stops. However, this is not an accurate perception. To understand it, one should look at how bad would be the impact of losing a hundred dollar note for a person who has several thousand dollars in his other pocket, compared to the impact of the same loss for the same individual if that was the last bit of money left with him. Thus, the concept of diminishing marginal utility is also applicable to money even though money is not an economic good that can be consumed on its own. It is a medium of value stored for exchange in future for other economic goods. One of the reasons that the principle of diminishing marginal utility seems to get diluted when applied on money is because a unit of money can be purchased different goods.

Whether the value or the utility can be measured and quantified is a matter of perennial debate. The theoretical presumption that it can be measured is referred to as cardinal utility or utility that can be measured and quantified. It is opposed to the ordinal utility theory that goes by the view that utility can only be measured in terms of relative preferences and ranked accordingly, but cannot be measured and quantified accurately.

Cardinal utility is the basis for drawing the two dimensional Diminishing Marginal Utility Curve, on scales representing quantity consumed (X axis) and utility derived consumption (Y Axis), wherein the marginal utility is represented by the steepness of the curve and can also be denoted as mU = dU/dQ, where mU is marginal utility; dU is change in utility; and dQ is change in quantity consumed.

Typically, the marginal utility curve rises steeply at first, and gradually flattens off, representing a continuous fall in marginal utility, till it becomes zero at a certain point, which is also known as the Saturation Point. Prior to the saturation point, consumption of every additional unit adds to the total utility, whereas consumption of additional units beyond the saturation point leads to Negative Marginal Utility, whereby the consumer becomes worse off. Thus, consumers are unlikely to consumer beyond the saturation point, even if goods are freely available to them.

A hypothetical unit called Utils can be used for measuring utility. However, in real life analysis, one can use other proxies like money that a person may be willing to pay for a marginal unit. This means that when measured in monetary terms marginal utility of different units of the same good will differ, and will also differ from the market price of that good, which is likely to be equal to the marginal utility of the last good consumed.

The theory of diminishing marginal utility tells us that within a given society, a person who already has sufficient units of that good will have little utility for more units, as compared to another person not having any units of that good. As a consequence, in a free market the person who does not have it would be willing to pay more for that good and thereby procure it, leading to a market driven efficiency in allocation of goods for consumption. Any Government intervention in this process can disturb and distort this market driven benefit to the society.

It also reminds us one of why economics is important for all public managers.

This is replete with fact that studying a major is one thing and applying that knowledge to real world situations is entirely another. Before you face the problem with experience paradox, that is, you need to show your experience to get a job and experience is not attained without a job or without performing those activities that are counted in the range of experience, you should consider to go for accounting internship..

Your monthly contribution for your future pension is one good way to prepare for your retirement but it’s not enough. Even when planning for your retirement, it is important to predict possible scenarios that might happen to you..

The statement, the boss is always right, is very common. People working in any organization under a manager or a superior hear this mantra very often.